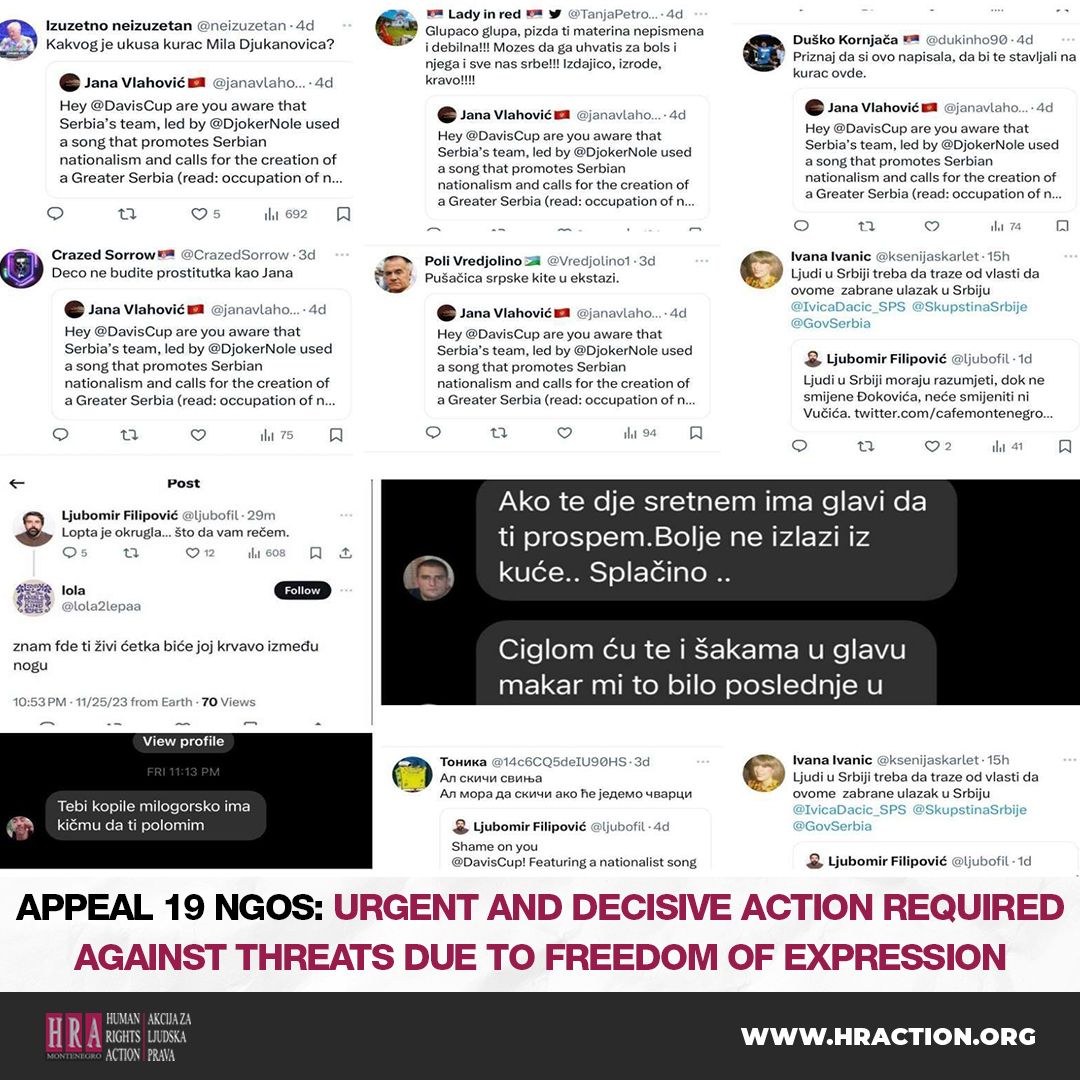

APPEAL 19 NGOs: Urgent and decisive action required against threats due to freedom of expression

28/11/2023

ANNUAL REPORT ON MONITORING JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS IN MONTENEGRO – JUNE 2022 – SEPTEMBER 2023

05/12/2023HRA’s Report “Liability for the Violation of Health Measures during the COVID-19 Epidemic in Montenegro”

On Friday, 1 December 2023, Human Rights Action (HRA) presented the draft version of its report entitled “Liability for the Violation of Health Measures during the COVID-19 Epidemic in Montenegro”, which is based on the analysis of decisions made by the state prosecutors’ offices and courts in proceedings that involved violations of measures prescribed by the orders of the Ministry of Health of Montenegro issued between 17 March 2020 and 4 March 2022.

The objective of the Report is to help the state organise a response to possible new similar challenges in the future based on previous experiences.

The Report stressed the importance of compliance with health measures to suppress an epidemic and preserve the right to life and health, as well as the need to respect the rules of the legal order in terms of restrictions of other human rights and equal treatment of citizens before the law.

The Executive Director of the HRA, Tea Gorjanc-Prelević, pointed out that human rights should not have been so drastically restricted by secondary legislation (orders) in the absence of a declaration of a state of emergency, and that violations of the orders should not have been criminally prosecuted since the European Convention on Human Rights requires that a criminal offence be precisely defined by law.

Gorjanc-Prelević also said that “following the example of Slovenia, Montenegro should reimburse the money and compensate all those who have been fined or imprisoned in criminal proceedings, and have these sentences deleted from their records”.

In criminal proceedings, 1,115 final decisions were issued for the criminal offence of ‘failure to comply with health regulations for the suppression of a dangerous infectious disease’. Out of the above number, 1,043 (98%) were convictions that involved 1,532 people. There were only 10 acquittals (0.9%).

Based on the analysed sample of 204 convictions (20% of all the decisions), a suspended sentence was imposed in most cases – 56.4%, a prison sentence in 14.2% of the cases, a fine in 17.2% of the cases, community service in 7% of the cases, and a court warning in 5.4% of the cases.

Prison sentences ranged from 30 days to three months. Fines ranged from EUR 200 to as much as EUR 4,500 in one case which was concluded with a plea agreement.

“The budget of Montenegro received at least EUR 208,000 from fines that were paid for violating health measures. Of the above amount, EUR 118,000 came from criminal proceedings,” said Gorjanc-Prelević.

The author of the Report, attorney Veselin Radulović, explained that violations of health measures were prosecuted in both criminal and misdemeanour proceedings, that criminal records contain information about convictions, and that this can pose a problem for many people, even today, especially for those who have been convicted in criminal proceedings.

He said that the regulation that defined the action of the criminal offence – failure to comply with the health regulations for the suppression of a dangerous infectious disease (Article 287 CCM) – was an order, which did not have the force of law, was being changed several times per month and would always come into force on the day of its publication. “The principle of legality, which is especially important when it comes to criminal proceedings, has been violated”, Radulović said, explaining: “We had an absurd situation where actions prescribed by the Law on the Protection of the Population from Infectious Diseases were treated as misdemeanours, while those that were prescribed by the Minister of Health were treated as criminal offences”.

He emphasised that the unequal treatment of citizens in the same situations and the unevenness of the penal policy have led to serious legal uncertainty.

He gave an example where the courts imposed suspended sentences, prison sentences and fines for the same act – namely, for driving a car. “For the same action, for example, the Basic Court in Danilovgrad imposed a prison sentence which was to be served in the premises where the defendant lived, while the Basic Court in Rožaje also imposed that sanction, as well as a court warning, a suspended sentence and a fine”.

The analysis also showed that the State Prosecutor’s Office selectively approached criminal prosecution for the same actions. In some cases it would initiate criminal proceedings for violating the orders, so those defendants were criminally convicted and sanctioned, and those convictions became part of their criminal records, while in some other cases, for the same actions, it would apply the institute of deferred prosecution and drop or dismiss criminal charges. “Consequently, for driving a car, the Basic Court in Podgorica sentenced three people to prison terms of 33 days each, while the State Prosecutor’s Office dismissed the criminal charges for the same act in another case after the reported person paid EUR 400 for humanitarian purposes”, said Radulović.

State prosecutors issued 1,072 decisions on deferred prosecution. Suspects were mostly obliged to pay the amount of EUR 100 to 3,000 in favour of a humanitarian organisation, fund or public institution. There was only one case of imposed community service.

Radulović said that prosecutors arbitrarily determined the amounts to be paid by different people, regardless of their financial status (which is otherwise taken into account when determining the amount of the fine).

“In the case where it was determined that the suspect should pay the maximum amount of EUR 3,000 it was stated that his financial situation was of a medium sort, and where it was determined that people should pay EUR 600 and 700, that their financial situation was poor. In one case, a person of good financial standing was ordered to pay the amount of EUR 300”.

Radulović also had an objection to the work of attorneys in these cases, because they insisted on concluding plea agreements based on the institute of deferred prosecution and accepted verdicts without filing appeals against them.

The Protector of Human Rights and Freedoms of Montenegro, Siniša Bjeković, said that it would be easier to resolve this complex matter if there was an appropriate catalogue of human rights and more precise definitions of this area in the Constitution itself, as HRA proposed some time ago. Bjeković added that whatever went on during the pandemic oscillated between two extremes: one – the adoption of measures in the interest of public health, and the other – respect for other human rights.

Bjeković reminded that the first measures were adopted before the epidemic was even declared, and that the first orders did not have a limited duration, which violated the principle of legality: “Sometimes, two acts with the same title would be published in the Official Gazette, which led to a situation where orders that had the same name and were published at the same time had different contents”. He said that the expected meritorious answer has not yet come from the European Court of Human Rights because applications are generally being declared inadmissible or the decision is still being awaited.

He highlighted the problem of the proportionality of the measures in terms of the restriction of certain rights, and the sentences that were imposed. He gave the example where a fine in the amount of EUR 1,200 was imposed on a hospitality facility in Vienna, Austria, and a fine in the amount of EUR 126 was imposed for violating the measures for the first time in Italy, while our country imposed much larger fines. “Citizens were confused about the sanctions imposed in this way, because there were examples where a person known in the public for extravagant appearance, who was caught in a luxury car, was issued a EUR 600 fine, while a clergyman, whose financial situation is obviously much worse, was issued a fine in the amount of no less than EUR 4,500″, said Bjeković. He explained that it is irrelevant whether an agreement had been reached about this or not, and that “the bottom line is that sanctions in criminal proceedings were disproportionate and uneven, at a time when misdemeanour sanctions for violating certain measures were not even prescribed”.

Bjeković added that at the time of COVID-19, public authorities (the National Coordinating Body for Infectious Diseases and subsequently the Council for the Fight against COVID-19) were balancing between economic welfare and public health, but he was of the opinion that the position of the Institute for Public Health, and health institutions in general, had to be decisive in terms of health risks, which was not always the case.

On the other hand, he pointed out that criminal sanctions are not dependent on the introduction of a state of emergency, and that they are present in the legislation of several European countries in legal situations when a state of emergency is not declared. He believes that they had to be proportionate and dissuasive, but that, at the same time, the existing circumstances in the state, the personality and behaviour of the defendant, as well as the gravity of the crime had to be taken into account, noting that this criminal offence requires intent as an element of the essence of the crime. He emphasised that misdemeanour liability should be primary, and that criminal liability should be reserved for more serious violations of health measures.

President of the Basic Court of Podgorica, Željka Jovović, said that the judiciary was functioning in extremely difficult conditions, especially during the period of COVID-19. In addition to regular proceedings, they were obliged to process additional urgent cases and organise on-calls. “At the time when the only thing we were hearing was ‘Stay at home’, judges were spending 12 hours in court, living a kind of parallel life”. Due to inadequate conditions in the court premises, they also had to provide protective equipment and masks for all defendants who were being brought to court. She said that initially they refused to order detention in cases that involved violations of health measures, but that they began to order them as a result of the development of the epidemic and the above court practice, plagued however by a constant dilemma about their justification. As a warning, they would publish data on the number of imposed detentions and sentences on the court’s website, accompanied by pleas to the citizens to respect the prescribed measures.

As for the criticism that defendants’ statements about their financial status were not being verified, Jovović said that they [judges] were faced with the absence of a public database on the financial status of citizens, and the procedures were urgent, so they established the financial status from the data obtained from the defendants. She also told an anecdote: “When asked about their financial status, members of the Roma population, who were dressed in modest clothing and had no income and assets, would respond that it was ‘good’…, while obviously well-off citizens tended, as a rule, to underestimate their own financial situation”.

She supported the recommendation on setting guidelines for punishment, both for the specific offence and for other criminal offences such as domestic violence.

The judge of the High Misdemeanour Court in Podgorica, Amra Grbović, who served in the Misdemeanour Court in Ulcinj during the epidemic, also pointed out the complexity of the functioning of the courts in emergency conditions. “The Law on the Protection of the Population from Infectious Diseases was the legal basis for the action of misdemeanour courts in specific cases. We all tried to be up to the task, we had urgent cases that required immediate work, we had to ensure that distance was kept in a confined space…”, said Grbović.

She also explained that the violation of the prescribed measures was initially qualified as a criminal offence, and that the law was later changed to prescribe misdemeanour offences for violating the measures during the COVID-19 epidemic. She, too, supported the adoption of guidelines for harmonising the case law.

Attorney Dalibor Tomović criticised the actions of some state prosecutors who ordered the detention of people who were brought in for violating the measures and proposed ordering detention if they refused to enter into a plea agreement or accept to pay a sum of money as part of the application of the institute of deferred prosecution. “In a situation where you were not sure whether you would get infected just walking down a street, let alone in prison, people had no dilemmas and would accept to pay their fines based on the principle of ‘take it or leave it’”.

The discussion of all the participants shows that it is necessary to further elaborate the difference between a criminal offence and a misdemeanour when there is an epidemic.

The lack of precision and the inconsistency of the misdemeanour and statutory frameworks are misleading both the holders of judicial offices and citizens. The actions of state authorities in practice must be harmonised by way of appropriate guidelines. The unequal treatment of citizens will otherwise be repeated, constituting a separate violation of human rights.

The Report was prepared as part of the project entitled “Access to Justice and Human Rights in Montenegro – Trial Monitoring Project 2021-2023”, which the NGO Centre for Monitoring and Research (CeMi) is implementing in cooperation with the NGO Human Rights Action (HRA). The project is financed by the European Union and co-financed by the Ministry of Public Administration of Montenegro.

President of the CeMI Board of Directors, Zlatko Vujović, announced that CeMI and HRA’s report on trial monitoring will be presented on Tuesday, 5 December, and that the Study on International Legal Aid, which analyses the actions of the Montenegrin state authorities in the above field, will be presented at the same time.

- Tea Gorjanc Prelević, izvršna direktorica NVO Akcija za ljudska prava

- Zlatko Vujović, predsjednik Upravnog odbora u NVO Centar za monitoring i istraživanje (CeMI)

- Veselin Radulović, autor izvještaja, advokat

- Siniša Bjeković, Zaštitnik ljudskih prava i sloboda Crne Gore

- Željka Jovović, predsjednica Osnovnog suda u Podgorici

- Amra Grbović, sutkinja Više suda za prekršaje u Podgorici

English

English Montenegrin

Montenegrin